At 8 a.m. on Oct. 25, 1975, Brazilian journalist Vladimir Herzog voluntarily reported to the São Paulo headquarters of the government’s intelligence agency and was never seen alive again. He died under torture. His death had profound repercussions, triggering a wave of protests and setting off a mass movement that played an instrumental role in bringing down the dictatorship that ruled Brazil from 1964 to 1985. Now, more than 37 years later, Herzog’s murder could be the case that finally sets Brazil on the path of investigating the crimes and abuses committed throughout its long dictatorship.

![]() (IPS) – At 8 a.m. on Oct. 25, 1975, Brazilian journalist Vladimir Herzog voluntarily reported to the São Paulo headquarters of the government’s intelligence agency and was never seen alive again.

(IPS) – At 8 a.m. on Oct. 25, 1975, Brazilian journalist Vladimir Herzog voluntarily reported to the São Paulo headquarters of the government’s intelligence agency and was never seen alive again.

The facilities he had been summoned to were just one of the detention and torture centers that were active during Brazil’s last dictatorship.

Herzog was editor-in-chief of the news department at the São Paulo-based television network TV Cultura, and had been called in for questioning by the Information Operations Department of the Center for Internal Defense Operations (DOI-CODI) for his alleged connections to the then-illegal Brazilian Communist Party (PCB).

He died under torture, but his death was made to look like a suicide by the military in an attempt to cover up the murder. A photograph released later showed Herzog hanging in his cell, but in a position that clearly revealed that the military’s suicide version was a farce.

The picture quickly became a symbol of the lies of the military regime.

Denounced by the Union of Professional Journalists of São Paulo, the death of “Vlado” – as he was called by friends and family – had profound repercussions, triggering a wave of protests and setting off a mass movement that played an instrumental role in bringing down the dictatorship that ruled Brazil from 1964 to 1985.

More than 37 years later, Herzog’s murder could be the case that finally sets Brazil on the path of investigating the crimes and abuses committed throughout its long dictatorship.

The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) of the Organization of American States (OAS) accepted a petition to open an inquiry to determine the responsibility of the Brazilian government in Herzog’s death, understanding that the state has not fulfilled its duty to investigate, prosecute and punish the perpetrators.

The IACHR will submit a report with its findings to the central-left administration of President Dilma Rousseff and, if the government fails to implement its recommendations, it will bring the case before the Inter-American Court of Human Rights.

In 2010, the court issued a ruling condemning Brazil for its failure to open up criminal inquiries and prosecute the perpetrators of the “arbitrary detention, torture and forced disappearance of 70 individuals during the dictatorship, including members of the Communist Party and peasants from the region,” who were part of the Araguaia guerrillas, a group that operated from1972 to 1974 in Marabá, state of Pará.

Attempts to bring the perpetrators of human rights abuses committed during the past dictatorship have been thwarted by a 1979 amnesty law (No. 6,683) passed by the military regime that pardoned anyone involved in political crimes or human rights violations in the period between Sept. 2, 1961 and Aug. 15, 1979.

Despite this obstacle, the Rousseff administration made great progress in this sense with the establishment of a National Truth Commission (created by Law No. 12,528) in 2011, mandated with investigating cases of forced disappearances of political opponents during the dictatorship.

This law was enacted in 2012 and sets a term of two years for the commission to complete its mandate. According to the document “Direito à Memória e à Verdade” (The Right to Memory and Truth), prepared by the government, at least 150 dissidents arrested or kidnapped by repressive forces during that period are still missing today.

Their relatives continue to search for their remains or for any information on the fate of their loved ones.

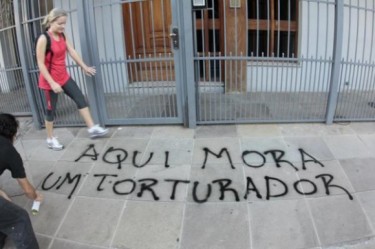

The truth commission is not the only effort to reveal the truth of the dictatorship’s abuses, as an increasing number of committees are being formed by state representatives, students and workers.

The truth commission is not the only effort to reveal the truth of the dictatorship’s abuses, as an increasing number of committees are being formed by state representatives, students and workers.

“Every action seeking truth and justice organized by the younger generations, to learn about and fight for human rights in Brazil is a new blow dealt against the dictatorship and the state of emergency,” Maria do Rosário Nunes, the presidency’s human rights secretary, said on Jan. 19 at the launching of the Journalists’ Truth Commission.

“Brazil has been slow to join the debate on truth commissions, which is aimed at recovering (collective) memory and obtaining justice for the deaths and disappearances committed during the dictatorship, and it’s far behind other countries, such as Uruguay and Argentina,” Beth Costa, general secretary of the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ), told IPS.

“But the IFJ and the National and Latin American Federation of Journalists welcome this firm decision by the government of Brazil,” she added.

Costa acknowledged the government’s difficulty in countering historical resistances, which date back to the period of national re-democratization.

“For years there was resistance from the military, which still has an impact through the seats held in parliament by the country’s conservative parties, many of which backed the military regime,” she said.

The members of the National Truth Commission face the challenge of filling in the information gaps that exist in the cases of disappearances and assassinations, and in the files that were put at their disposal for the investigation, which may not be complete despite the Data Access Act that Rousseff passed along with this specialized body.

“Some 25 journalists were killed during the dictatorship,” journalist Audálio Dantas told IPS. A former president of the Union of Professional Journalists of São Paulo, Dantas headed the protests to expose Herzog’s staged suicide.

Dantas, who currently heads the National Commission of Brazilian Journalists for Memory, Justice and Truth, detected major gaps in the government’s files, which he consulted as part of the research for his book “As duas guerras de Vlado Herzog” (The Two Wars of Vlado Herzog), published in 2012 by Editora Civilização Brasileira.

When he tried to access the case files, he was asked to furnish a copy of Herzog’s death certificate.

“This demand was not only absurd, it was disrespectful to Vlado’s memory. Meeting this request would have entailed accepting as true the cause of death recorded by the certifying doctor, Harry Shibata, a DOI-CODI collaborator, who signed the certificate without ever seeing the body, ruling it a suicide,” Dantas wrote in his book.

“The Truth Commission finally succeeded in having the certificate amended,” he told IPS. Now it states that Herzog’s died as a result of “injuries and abuses suffered while in the São Paulo second army facilities (DOI-CODI).”

Beth Costa believes that reconstructing the history of the journalists who were forcefully disappeared by the dictatorship will be a key step in rebuilding the country’s collective memory and in the process of re-democratization of its institutions, especially at a time in which Brazil is listed among the countries with the greatest number of journalists murdered in the line of duty.

Freedoms such as the right to report freely and safely and the right to be informed are once again at risk. This was made patently clear when newspaper reporters André Caramante, of Folha de São Paulo, and Mauri Konig, of Paraná’s Gazeta do Povo, were forced to leave the country after receiving death threats for exposing police misconduct.

Dantas recalled that, in addition to guaranteeing the safety of all media professionals, the government must weed out certain elements from police forces, which were left over from the dictatorship and form extermination squads.

“It’s shameful that after successfully fighting off political repression we are now incapable of battling the repression that is a daily reality in the peripheries of our large cities and inside our police stations,” he said.

“The government is afraid to tackle this problem, perhaps because most middle and upper class people believe that seizing and executing without trial is an acceptable practice. It’s the country’s biggest shame today,” he charged.