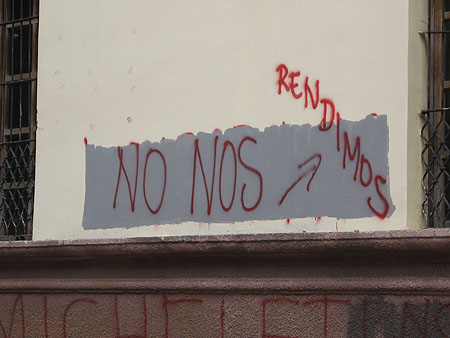

Even as tireless Honduran protesters approach their 100th day of resistance, continuing to avoiding police tear gas and attend funerals of slain resisters, some facets of quotidian Tegucigalpa life continue under the dictatorship. Yet the literal writing on the walls deny the state of calm that the coup leaders claim exists and expose the state of exception that they impose. These photos capture the ongoing conversations in a shrinking space for expression.

Source: Quotha.net

Even as tireless Honduran protesters approach their 100th day of resistance, continuing to avoiding police tear gas and attend funerals of slain resisters, some facets of quotidian Tegucigalpa life continue under the dictatorship: cars cram into traffic-filled streets, those Hondurans with jobs go to work, and wealthy consumers hit the shopping malls. To maintain this facade of control, on September 27th the Micheletti dictatorship issued a decree dissolving fundamental rights such as the right to assembly and free speech, and the following day closed the critical media sources in the country by force. Yet the literal writing on the walls deny the state of calm that the coup leaders claim exists and expose the state of exception that they impose. These photos capture the ongoing conversations in a shrinking space for expression.

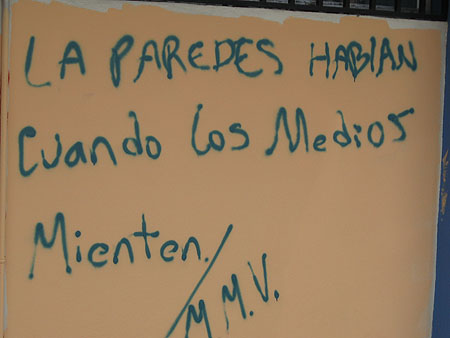

“The Walls Talk When the Media Lies”

Since June 28th, large scale media outlets owned by businessmen benefiting from the coup—such as the newspaper El Heraldo—have consistently misreported and ignored the violent repression of coup resistance in Honduras. On September 28th, Roberto Micheletti’s de facto government shut down Radio Globo and Canal 36, eliminating the most widely available outlets critical of the coup. While some members of the resistance look to international media to report the realities of dictatorship in Honduras, many foreign news outlets mirror the ambivalent responses of foreign governments such as that of the United States.

"El Heraldo 666"

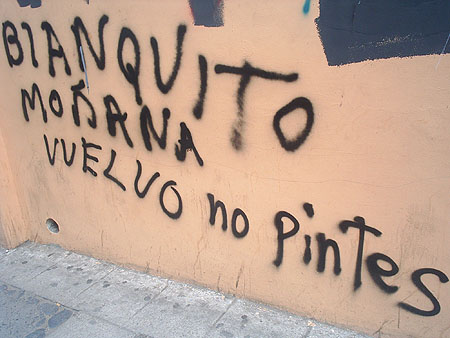

“Blanquito, I’ll be back tomorrow don’t paint over this.”

Resistance members refer to Micheletti supporters as ‘blanquitos’ because of the white shirts they sport in an ironic attempt to represent “peace” and “democracy.” The term also links today’s struggles with the racial heritage of the oligarchy and the legacy of European oppression in Honduras.

Red and white flags of the Liberal Party (the party of the coup administration) are reclaimed by the resistance movement in support of President ‘Mel’ Zelaya.

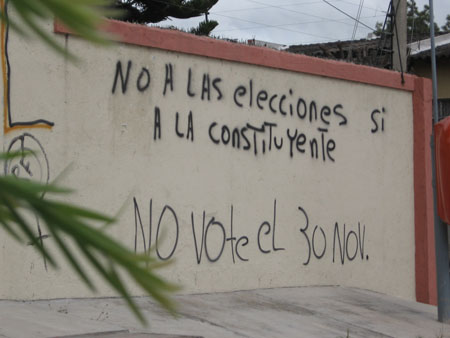

“No to the elections, yes to the constitutional assembly”

Before Zelaya’s return to the capital on September 21st, the resistance was planning a national strike to demand constitutional reform through a constituent assembly. For the resistance, Zelaya’s presence in the country represents the nearing possibility for constitutional reform. In response, the coup leaders have been scrambling to gain international recognition for the November elections.

“Mel is necessary / Mel is urgent”

The phrase ‘Urge Mel’ has been revived from a song used in his 2005 election campaign. The country’s coup-supporting business elites, led by Adolfo Facussé, recently proposed Zelaya’s return to the presidency in hopes of gaining U.S. recognition for the November election. Their plan is a thinly masked maintenance of coup control, as it also calls for limitations on Zelaya’s power, his prosecution under charges of stealing money, and the installation of Micheletti as a Congressman for life.

“Mel-gar is a thief”

This layered message reclaims the statement, ‘Mel is a thief,’ by changing the name to that of General Juan Melgar Castro, who overtook the Honduran presidency through a military coup in 1975. Like Melgar, General Romeo Orlando Vasquez Velasquez, the military leader of Zelaya’s overthrow, received training at the U.S. Army School of Americas.

“My country free or death”

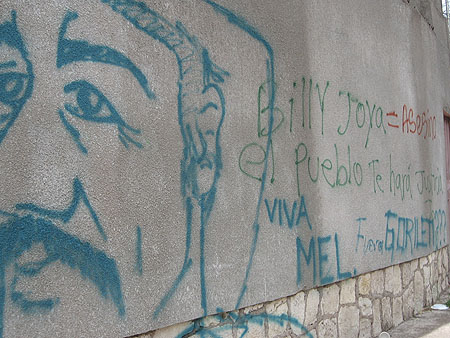

Zelaya image, “Billy Joya is an assassin/the people will do you justice,” “Long live Mel”

Billy Fernando Joya Améndola , the ministerial adviser on security for the coup regime, served in Battalion 3-16, an elite army death squad responsible for the disappearances of at least 180 Hondurans in the 1980s.

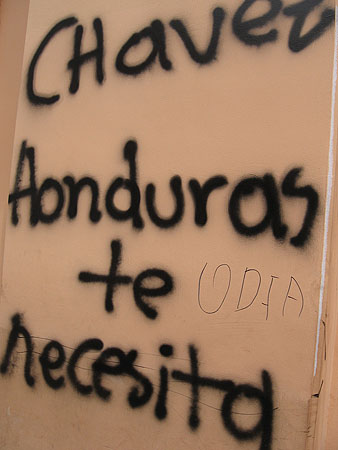

"Chavez, Honduras needs you [need crossed out and replaced with hate]”

Public justifications of the coup government focus on a poll that Zelaya proposed as a way to initiate discussion of constitutional reform. To provoke panic about a removal of presidential term limits in Honduras, conservative media have called this a “Chavez-style” move, but juridical analysis clearly shows that the poll established no implications for re-election.

“Out with the coup regime,” “Sold out journalists your day will come,” “Micheletti you are not my president! Signed, The People.”

These declarations are scrawled across the Congress building in Tegucigalpa’s city center.

“Honduras is Repressed,” “Censorship”

These pieces of masking tape come from activists who place tape over their mouths to draw attention to the censorship of the Honduran media and people.

“We will not give up”