Tanya Kerssen does a good job of describing the several peasant unions in the Aguan and the divisions caused by their different histories and experiences based on varying levels of land titles and the levels of violence and repression on them. However, they do unite in opposition to the coup and against the coordinated violence of the police, military, and the paramilitary thugs of the big landowners, while also forming a pillar of strength within the FNRP.

In June 2011 when Tanya Kerssen and I led a delegation of human rights accompaniers to the Aguan Valley of Honduras, we did not know that we would, ourselves, play a cameo role in the life and death struggle for land in the Aguan. On July 1, 2011, our delegation of US and Canadian residents stood between 40 heavily armed police and the people of Rigores who they intended to illegally evict. The week before, the police had burned and bulldozed the homes, school, and two churches of this seven year old peasant cooperative. The police had returned to drive the people off their land so that their absence would weaken their legal claim. For 3.5 hours we were locked in a tense stand-off before the police finally received instructions to withdraw. When I returned to the community a year later, all but three families had rebuilt their homes, replanted their corn and beans, and replaced some of their animals.

In June 2011 when Tanya Kerssen and I led a delegation of human rights accompaniers to the Aguan Valley of Honduras, we did not know that we would, ourselves, play a cameo role in the life and death struggle for land in the Aguan. On July 1, 2011, our delegation of US and Canadian residents stood between 40 heavily armed police and the people of Rigores who they intended to illegally evict. The week before, the police had burned and bulldozed the homes, school, and two churches of this seven year old peasant cooperative. The police had returned to drive the people off their land so that their absence would weaken their legal claim. For 3.5 hours we were locked in a tense stand-off before the police finally received instructions to withdraw. When I returned to the community a year later, all but three families had rebuilt their homes, replanted their corn and beans, and replaced some of their animals.

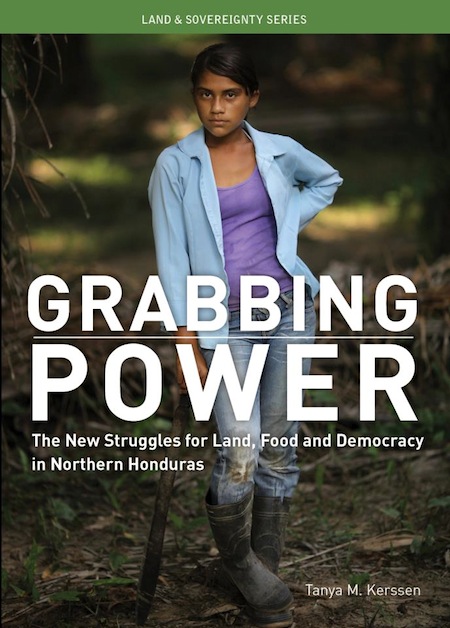

Kerssen, the Research Coordinator at Food First/Institute for Food and Development Policy, doesn’t write about that incident in her book Grabbing Power: The New Struggles for Land, Food and Democracy in Northern Honduras (Food First Books 2013), nor should she have. We, after all, returned to our privileged lives in the North. The Mestizo peasants and their Afro-Indigenous neighbors don’t get to leave. They are home; the only home most of them have ever known. Every day they risk their lives and the lives of their families because, as we were told by a Garifuna leader, “Our backs are to the wall. We have nowhere else to go.” It is their story that Kerssen tells in Grabbing Power, and a powerful story it is.

Honduras is a country that few in the US knew anything about prior to the June 28, 2009 coup that ousted democratically-elected President Manuel Zelaya. Hundreds of thousands of US solidarity activists have visited or know a lot about Nicaragua, El Salvador, and Guatemala, all of which border Honduras, but for many Honduras has been a blank slate. I remember in the 1980s we on the staff of the Nicaragua Network used to call it the USS Honduras for its US domination and its use as a safe haven and training center for the US-funded Contra terrorists.

But even then Honduras peasant cooperatives in the fertile Aguan Valley were organized and struggling for their rights to own the land that they had cleared and cultivated. Kerssen takes us through their compelling story beginning when the military dictatorship of the 1960s and 1970s opened up the virgin rainforest of the Aguan Valley to be cleared and put into agricultural production, specifically African oil palm, by cooperatives. The dictatorship didn’t do this because they cared about peasants, but rather to avert a social explosion by landless peasants shut out of access to land because most of the tillable land in Honduras was controlled by United Fruit (now Chiquita) and Standard Fruit (now Dole).

Honduras was the original “Banana Republic” and was also an important US military platform. In fact, Kerssen explains that for much of the Twentieth Century its government didn’t change hands because of Honduran political actors, but because the US banana companies and the US military competed for control of the government. Their competition was “arbitrated by the US Department of State.” The fact that agrarian reform came under a military dictatorship and the land was stolen from them under a “democracy,” is why doubts about democracy are pretty deep-seated among the peasantry, according to Kerssen.

If Honduras is now a failed state, it was hardly even a functioning state in the first place in terms of its citizens seeing themselves as actors in a national project. That makes all the more remarkable the convergence of diverse social movements, labor, teachers, LGBT activists, indigenous, artists, and perhaps most importantly, the peasant cooperative unions, in the wake of the 2009 coup. Over three years later they remain united under the banner of the National Front for Popular Resistance (FNRP). There is not, however, total unity over the FNRP’s decision to compete electorally in the 2013 general election under the banner of the new Liberation and Refoundation Party known as LIBRE. Zelaya’s wife, Xiomara Castro, a resistance leader in her own right, is LIBRE’s presidential candidate and leads in public opinion polling. However, despite the fact that all the organizations that comprise the FNRP are not part of LIBRE, there remains a high level of unity around the demand to “refound the State.”

Kerssen does a good job of describing the several peasant unions in the Aguan and the divisions caused by their different histories and experiences based on varying levels of land titles and the levels of violence and repression on them. However, they do unite in opposition to the coup and against the coordinated violence of the police, military, and the paramilitary thugs of the big landowners, while also forming a pillar of strength within the FNRP.

In contrast to the life and death struggles of most of the cooperatives in the Aguan, Kerssen tells about the few cooperatives which never lost their land, such as Salama where today every family lives in dignified housing with internet, and Prieta where every student’s education is paid for through college and where not a single young person has migrated to the United States, “an extreme rarity for rural Honduras.” These cooperatives are prosperous enough to invest some of their land in food production with the goal of achieving food sovereignty. These cooperatives have also been an important source of money and food for the struggling land occupations. They stand as an example of what peasant cooperatives could be without the violence and rapacity of Miguel Facusse, owner of the Dinant Corporation, and his fellow land grabbers in Honduras’ oligarchy.

Kerssen is an expert on food sovereignty and peasant agriculture. She detests the monoculture industrial plantation export-driven model demanded of countries like Honduras by neoliberal economic orthodoxy. Ye,t she does so without being judgmental about the decisions peasants must make. She writes:

Aguan movements may not have rejected oil palm production or fully embraced agroecology, but they are engaged in an ongoing discussion about food sovereignty among themselves and with transnational movements like Via Campesina. But in the Aguan (and indeed everywhere), food sovereignty has to be pragmatic. It has to work now if imperfectly, in the embattled context in which peasants find themselves.

Grabbing Power is very readable and accessible book that does not require a high level of knowledge about Honduras, peasant agriculture, or the food sovereignty movement in order to be a valuable source of knowledge and understanding of this troubled country where acts of incredible courage and determination are taking place daily outside the notice of even most of us who would describe ourselves as Latin America solidarity activists. Grabbing Power helps fill in the formerly blank slate for us.

Read the Introduction of Grabbing Power HERE

Chuck Kaufman is national co-coordinator of the Alliance for Global Justice, active in the Honduras Solidarity Network (US), and has led several delegations to Honduras.