From August 12-16 the zapatistas opened the doors to their caracoles, communities and hearts to 1630 students enrolled in the first grade of “the escuelita (the little school): freedom according to the zapatistas.” The escuelita didn’t have formal classrooms with a rigid schedule and teachers imparting their knowledge. Instead it featured immersion based learning, grounded in the daily tasks of constructing autonomy. This included grinding corn, weeding onion crops, collecting firewood, and washing your clothes in the river.

“The only thing that you need, objectively, to attend the zapatistas’ little school is Disinclination to talk or to judge, Willingness to listen and watch and a well-disposed heart.” – Comunicado VOTÁN II. The Guardians. Subcomandante Marcos

“The only thing that you need, objectively, to attend the zapatistas’ little school is Disinclination to talk or to judge, Willingness to listen and watch and a well-disposed heart.” – Comunicado VOTÁN II. The Guardians. Subcomandante Marcos

From August 12-16 the zapatistas opened the doors to their caracoles, communities and hearts to 1630 students enrolled in the first grade of “the escuelita (the little school): freedom according to the zapatistas.”

The escuelita didn’t have formal classrooms with a rigid schedule and teachers imparting their knowledge. Instead it featured immersion based learning, grounded in the daily tasks of constructing autonomy. This included grinding corn, weeding onion crops, collecting firewood, and washing your clothes in the river.

All students in the escuelita were received at the CIDECI, an autonomous indigenous learning center based in San Cristobal de las Casas. From there, each student was assigned to one of the five caracoles: La Realidad, Oventic, Morelia, Roberto Barrios and La Garrucha which are the centers of the “Juntas de Buen Gobierno”, which loosely translates to The Good Government reunions.

Days before, the caracoles celebrated 10 years of their existence with a grand party in each region. The escuelita was a natural extension of this historic anniversary in which the compas (short for compañero) would not only celebrate their creation, but also impart all the advances they have made in their construction of autonomous government.

I was assigned to Roberto Barrios, located in the northern region of Chiapas, close to the historic Mayan ruins Palenque. Our caravan arrived at 10 p.m. after a long drive through the Chiapan hillsides and jungles. At best we thought a few zapatistas would greet us and that together we would dine with tortillas and beans. Instead we were greeted by hundreds of zapatistas bearing their trademark balaclavas and paliacates (red paisley bandannas), pronouncing “long live the students and teachers of the escuelita.” Together we sang the zapatista anthem and ate delicious stew. For many of the students, myself included, this was the first time that we had the opportunity to stand side by side with the rebel fighters that had so inspired us for close to two decades.

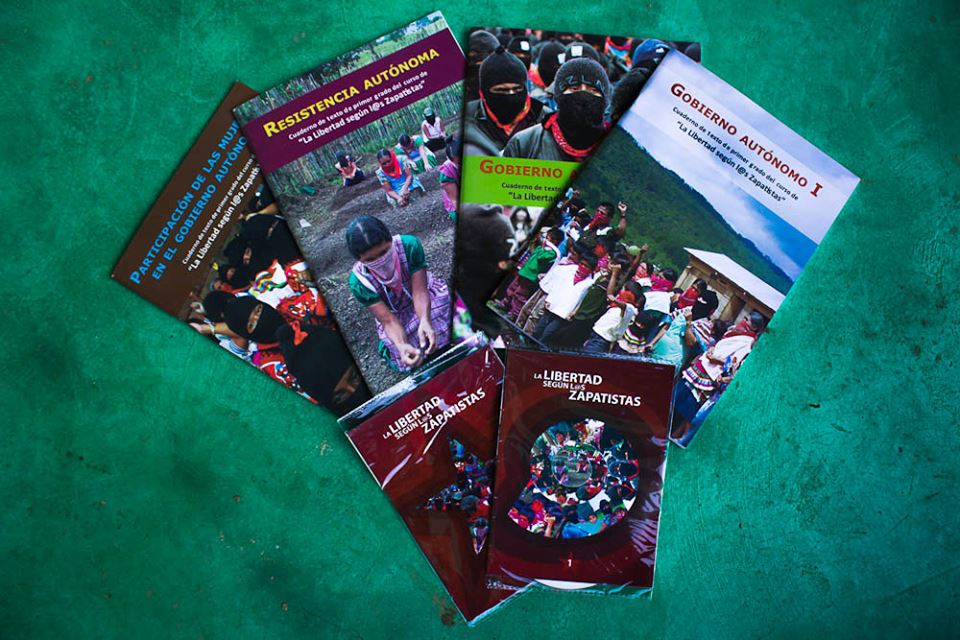

Once we were rested up from our long journey we all gathered together to learn more about the processes of autonomy. Each student was given, for a modest recommended donation of 100 pesos (equivalent of $8.50 USD) a packet of books and DVDs. The titles were Autonomous Government 1 and 2, Autonomous Resistance and The Participation of Women in Autonomous Government.

Once we were rested up from our long journey we all gathered together to learn more about the processes of autonomy. Each student was given, for a modest recommended donation of 100 pesos (equivalent of $8.50 USD) a packet of books and DVDs. The titles were Autonomous Government 1 and 2, Autonomous Resistance and The Participation of Women in Autonomous Government.

As with most projects in zapatista life, they were produced collectively by compiling the stories of members of the communities in the five distinct regions each governed by their own Caracol. The teachers who helped draft the books, introduced us to them explaining how the 3 levels of zapatista government work on the local, municipal, and zone levels. The government representatives are chosen from all zapatista municipalities and serve three year terms. There is a strong desire for gender equity in the Juntas de Buen Gobierno, yet the zapatistas acknowledged that they are still struggling in that area and that the majority of the representatives are male.

Speaking before the students in Roberto Barrios, one zapatista teacher stated: “The laws of the bad government don’t function here, they can’t enter our communities. Our governments are our dream. We are not thinking of operating with them for a few people but for thousands of people.”

The teachers went on to explain how their system of government even has its own justice and banking system. A story was recounted in which a “pollero”, or human trafficker of Central American migrants who passed through zapatista communities on their journey north, was captured. Once caught, he was not incarcerated; instead he was required to work 6 months with the zapatistas doing carpentry work. The former migrant trafficker at the end of his 6-month work stint thanked the zapatistas, saying “it wasn’t a punishment, it was a great help because now I have learned a work trade that I can continue to use.”

The zapatista bank was formed so that when a compañero or compañera gets sick they would be able to obtain a loan to pay for medical costs and pay back the money with a very low interest rate, and in the case that they die, the family does not have to pay back the loan.

While these lessons were shared formally from the Caracol stage, the true teachers of the escuelita were the Votánes. Each student was assigned their own Votán– also known as a guardian- who would accompany through the entire learning process, and serve as a translator from Tzeltal, Tzotzil, Tojolabal or Chol, into Spanish.

It is important to note that the majority of Votánes were younger than 25-years-old, meaning that they were born, or at least raised after the ‘94 uprising. The “other world” that we dream of constructing, is the only world they have known. They breathe and live autonomy, with a profound sense of collectivity and the education that has been bestowed on them from the autonomous Zapatista schools.

Each student resided with a family in a different zapatista community, accompanied by their Votán. Some communities were what many would call “utopic” with solar power, composting bathrooms, extensive food cooperatives, and well-constructed houses. Some communities were located right off a well paved highway and some were only accessible via a four hour hike through the jungle, crossing rivers, where there was no electricity or running water, besides local creeks. Some communities were exclusively Zapatistas and others a mix of zapatistas, “partidistas”, what the zapatistas call those of civil society who believe in the political party system and paramilitaries.

Our community, Comandate Abel, located in the municipality La Dignidad, was accessible via a muddy highway, which allowed us to advance at a maximum 1km an hour. It led us into a lush green valley full of corn dotted hillsides. Entering the community we crossed the beef cooperative where all members of the community tend to the land and take turns carrying for the health of the cows. Beyond the cow field was the elementary school, that serves all the youth of the community teaching basic skills and zapatista concepts of autonomy.

Comandante Abel is an exclusively zapatista community that lives under constant threat of the paramilitary group ironically named Peace and Justice.

While most students stayed with families, the security conditions were less than favorable in this community and us 20 students and Votánes stayed in one building together for safety concerns. Cell phone service doesn’t reach this area, but the Zapatistas have an internal radio system for emergency communication.

In the morning we headed out into the fields. We weeded an onion field, harvested yucca, sugar cane, and corn, and picked mandarin oranges and grapefruits. My Votán Rosario explains to me, “this is how we pass our days, we wake up and head to the fields to look for our daily sustenance, to harvest what our family will eat that day.” Talk about “fresh”, “local”, “seasonal” and “organic”- the zapatistas have it without the special terms. Little is prepared on the firewood stove that wasn’t harvested that day from the fields. Tortillas are made daily which entails harvesting the corn, shucking it, plucking the grains, cooking the grains with cal to start the process of nixtamalization, hand grinding it, and kneading and flattening it by hand.

In the morning we headed out into the fields. We weeded an onion field, harvested yucca, sugar cane, and corn, and picked mandarin oranges and grapefruits. My Votán Rosario explains to me, “this is how we pass our days, we wake up and head to the fields to look for our daily sustenance, to harvest what our family will eat that day.” Talk about “fresh”, “local”, “seasonal” and “organic”- the zapatistas have it without the special terms. Little is prepared on the firewood stove that wasn’t harvested that day from the fields. Tortillas are made daily which entails harvesting the corn, shucking it, plucking the grains, cooking the grains with cal to start the process of nixtamalization, hand grinding it, and kneading and flattening it by hand.

The following day the students, guardians, and all members of the community heading to the cow fields to sharpen our machetes and hack at the weeds. Cleaning the cow field by hand would have been an impossible task for a few people, but many hands make light work and it is the zapatistas cooperative spirit that allows grand projects like this to be possible.

Fernando, who joined us from a neighboring Zapatista community that operates a honey cooperative said, “We resist the capitalist system with our cooperative projects. We are not asking for government support. These cooperatives are for our liberation and also on an international level for people all across the world.”

It is this collective force and the fruits of their cooperative labor that made the escuelita possible. Furthermore, this school wasn’t funded by some elite foundation, an NGO, the Basque government, or some Italian solidarity group. All of the labor to pull off this enormous endeavor was donated whole-heartedly by the compas who pooled money from their cooperative endeavors to fill the gas of the 100+ transport vehicles and pooled food to fill the stomachs of all the participants.

Living along side the compas for these few days gives us the smallest glimpse into the reality of life as a zapatista. While driving to the community we are stopped at a military checkpoint, which dot the entire state of Chiapas, and while we are only asked basic questions and held for 15 minutes, it gives us a little insight into what its like to be part of an insurgency living in a heavily militarized zone.

After the escuelita the Indigenous Revolutionary Clandestine Committee – General Command of the Zapatista Army for National Liberation, released a communique denouncing military plane flyovers, stating that: “Maybe, serving their masters, the Mexican soldiers are spying for the US government, or, maybe the North American planes are doing the work of spying directly. Or maybe the soldiers want to see what is taught in the zapatista communities that they have attacked so much, but have been unable to destroy.”

We had a meeting with the entire community and in their native language Chol explain to us the history of the community. In a communique Subcomandante Marcos explained why we could only understand what the community said via our Votán.

“You will of course be left with the doubt as to whether your question was adequately translated and if the answer you got is the same as that which the teacher gave. But, isn’t that exactly what an indigenous person is subject to with a translator in the government courts of justice?”

The community leaders of Comandante Abel explained how on September 6, 2012 heavily armed paramilitaries arrived at the corn fields and evicted the zapatistas. One woman recounted how they had to take refuge in surrounding hillsides, carrying numerous children in their arms. They explained how this displacement created food insecurity as they no longer could access their crops that they had cultivated for years, and were left with nothing to feed their children.

A beautiful river runs alongside the community, yet the community can’t access it, and instead are forced to wash their clothes, dishes, and corn in a muddy water hole or small creek. While we celebrated our last night in Commandate Abel with a big feast from the cow that was just killed for us from the cooperative, we glanced over to the neighboring hillside where the paramilitaries have erected a bright red flag. Last time they erected one flag, followed by two more, once the third was erected they attacked the community.

While we were accompanied by our Votánes, families and books, some questions still remained and when we returned to the Caracol, zapatista maestros responded to our inquires. The answers mostly addressed zapatista terms and names and failed to explore deeper issues. While one student commented to me “how you gonna criticize them in their own house,” others wondered “why they didn’t respond to their questions wondering if divorce or separation was actually practiced in communities, or what happens if a Zapatista has interest in studying outside of the community.”

The zapatistas did assure us that we could not be zapatistas, nor live in their communities, but perhaps for many of the students that was not their intention. For some, the intense labor we participated in to provide one’s daily sustenance broke some of the romanticization of life in zapatista communities.

But, the zapatistas have never asked us to adopt their way of live. What they do ask of us is to stand with them in their struggle and that for “each of us struggle where you are and construct your own autonomies where you can.”