As the conflict over educational reforms in Guatemala’s escuelas normales rages on, police violently evicted student protesters on July 2 from their occupation at Industry Park and various schools throughout Guatemala City, in an ongoing campaign to repress the movement. In the morning, reports described that four police squads detained up to eight students, while 12 more were sent to the hospital. Allegations of sexual aggression toward young female protesters also circulated via independent media outlets.

In San Juan Sacatepequez during an anti-militarization march on June 30, women hold a sign that reads: “We need more teachers, not military brigades.” Photo by the Centro de Medios Independientes – Guatemala.

Source: Waging Nonviolence

As the conflict over educational reforms in Guatemala’s escuelas normales rages on, police violently evicted student protesters on July 2 from their occupation at Industry Park and various schools throughout Guatemala City in an ongoing campaign to repress the movement. In the morning, reports described that four police squads arrived at the park with Minister of the Interior Mauricio Lopez Bonilla, and detained up to eight students, while 12 more were sent to the hospital. Allegations of sexual aggression toward young female protesters also circulated via independent media outlets as the normalista students prepared for potential further evictions and continued to demand negotiations with the Ministry of Education.

The escuelas normales in Guatemala are schools located throughout the country’s 22 departments that train young students to be teachers. The teacher’s certification has long been one of the only professional degrees accessible to Guatemala’s rural and indigenous youth who cannot afford higher education. In a country where only 2 percent of the population receives a university education, educational opportunities remain an important indicator of and contributor to the Guatemala’s vast economic and social inequalities. The normalista movement, for the last two months, has been using direct action to oppose a proposed two-year expansion of the magisterio program, including the occupation of their schools which have suspended classes in Guatemala City.

The magisterio degree in Guatemala, or teacher’s certification, is a five-year program that includes Guatemala’s high school equivalent. Students usually start the program around age 13 or 14, and finish around age 18. The people currently occupying their schools and demanding fair negotiations with the government are young adolescent youth.

“Study and learn, so that we will never become police!” chanted supporters of the students outside of the Rafael Aqueche Institute in Guatemala City, as police surrounded the entrance to the building at dusk. Faced with imminent violence, the students at Aqueche agreed to be escorted out of the building by volunteer firefighters and taken to a safe place.

Police prepare to evict the Aqueche Institute on July 2. Photo by the Centro de Medios Independientes – Guatemala.

“The police stated that if we didn’t leave, we would suffer the consequences and in Guatemala we know just what that means,” explains Sandra Xinico of Students for Autonomy at the University of San Carlos. “What we can see here is repression again against the students. They were doing a peaceful occupation. Just now, the Minister of the Interior said that they didn’t use force, but this is violence. This is what we live here in Guatemala and we are tired of what’s happening in this country.”

At the eviction, Bonilla reaffirmed his resolve to end the occupations. He repeatedly denied the use of force to evict students, but was recorded responding, “I would love to.”

“This has been the plan since 1998, since the signing of the peace accords,” Bonilla stated. “So what we have to do is take back control of the schools, put everything back in order and put an end to the anarchy.” As the police retook the Institute, students reaffirmed their demand for fair negotiations and a different proposal for educational reform in Guatemala.

Education for whom?

The Normales Student Movement alleges that the reforms are geared toward a de facto privatization of education in Guatemala. The idea of private versus public in this context goes beyond the question of who administers education. To the students of the normales, it is about access. Protesters claim that a two-year extension of the curriculum would force many students to drop the degree because they would not be able to afford the additional cost.

“A lot of times we stop studying because we say, ‘I’m going to save some money and then go back to school,’ or we just stop because we have to support our families,” explains Enma Catu of the Mojo Maya Indigenous Youth Movement. “Very often we leave our degree in the middle, because we cannot afford to continue.” According to El Periódico, only 20 percent of Guatemala’s high school-aged population attends high school, or diversificado.

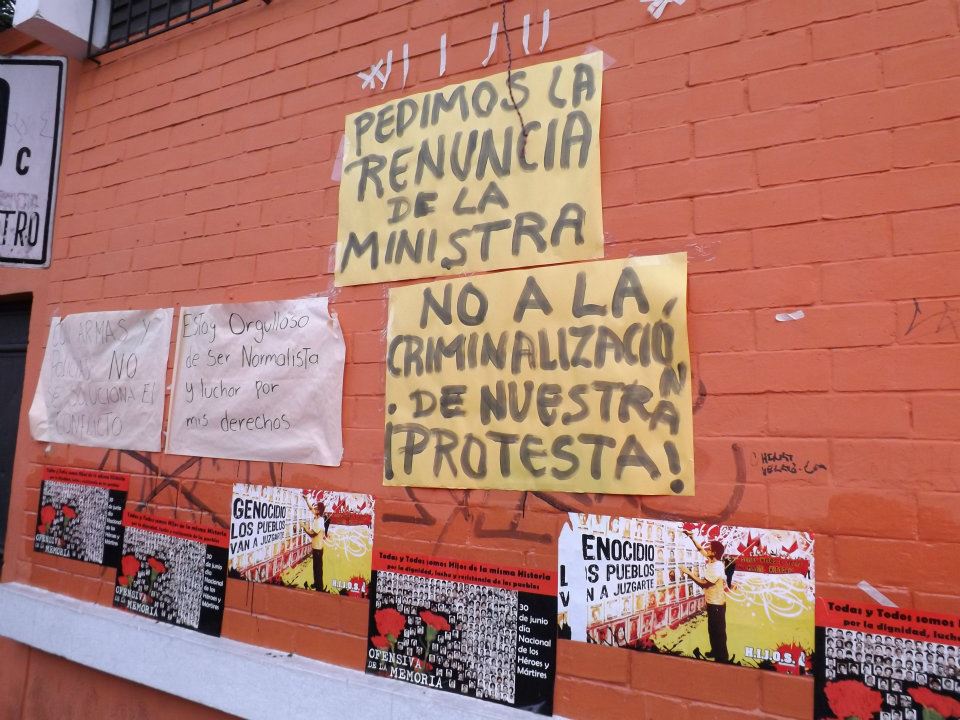

Signs outside the Aqueche Institute read “We ask that the Minister step down,” and “No to the criminalization of our protest.” Photo by the Centro de Medios Independientes – Guatemala.

According to Enma, Article 74 of the Guatemalan Constitution protects the right to free public education, while privatized education is only available to those who have the money to pay for it. An exclusionary national educational system cannot be considered truly public if it upholds the privilege of the wealthy over the vast majority of people in the country.

“I am sure that everyone would be in favor of the two-year increase, if it were free,” explains Enma, who calculates that each additional year of schooling could cost a family 10,000 to 12,000 quetzales (approximately US$1,200-1,500) between materials, fees, housing and transportation.

Concerns that more private schools are springing up nationwide also fuel the fear that diminishing the accessibility of the normales will lead to privatization. A report from the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Right to Education Vernor Munoz in 2008 noted that around 80 percent of high school education in the country was already in the hands of private institutions. As Enma explains:

We talk about privatization because about 15 years ago, education was just about registering your name and your grade, and that was it. But then the government of Arzu, who is now the mayor of Guatemala City, started privatizing education by establishing the registration fee… There is evidence that the government has been turning over education to the private sector, private companies. We see more companies in different departments that now say they provide education. So now we’re conditioning our parents to work for those large companies so that they can have the right to education. That’s part of privatization. For example, there are over half a million kids in Guatemala who don’t go to school and that’s because there are more private schools than national schools… If students stop being able to complete the magisterio degree then it will be done away with all together. The private schools will be the ones left and it’s clear that those who can study there are middle and upper class people, who have power.

The normales’ significance is also cultural and political. The accessibility of the teachers’ certification impacts not only who gets to become teachers, but how education happens in Guatemala. With a teaching force increasingly wealthy and non-indigenous, many fear that the bilingual and culturally relevant education in Mayan communities, which has been brought about through a long struggle, will deteriorate.

“We could see a resurgence of problems of the past, like the ones our parents had to suffer through, where they were prohibited from speaking their native Mayan languages. That’s also a risk that could affect us as indigenous youth and that’s the majority of us,” states Enma.

Others point to a lack of democracy and consultation around such significant reforms to the education system. As Sandra explains:

Some of us have had access to the plan, but only after the students rose up and took the schools. Everything is brewing behind the backs of the people… We want [a reform] that will serve the real needs of the people, not one that is imposed on us. We can’t take any more imposition in this country.

Strikes in education are always controversial, given that they paralyze a process that is highly valued by society. This is something the government and mainstream media have certainly capitalized on. But according to Enma, the protesting students have more support than the media lets on:

The resistance is most visible in the capital, but the departments have also made their declarations… In Huehuetenango, Chimaltenango, Solola, Quiche, Alta Verapaz… but we know the media often ignores this part.

“History has repeated itself many times in this country, unfortunately,” concludes Sandra, as supporters walk away from the Aqueche Institute. “New generations don’t understand the sad and bloody history of this country. Right now it’s themagisterio and tomorrow it will be many other things. What will the Guatemalan people do? What will we do together?”

The day after the evictions, normales students blocked the InterAmerican Highway in the Departments of Totonicapan and Chiquimula, showing that students in the capital were not alone. This morning 44 indigenous, campesino, union, and women’s organizations held a press conference coordinated by the Committee for Campesino Unity to support the normales student movement and denounce Monday’s repression. They are calling on a massive march of solidarity in Guatemala City for July 5 that would unite the campesino and indigenous movements of rural Guatemala with the students’ struggle.