The imposing Rio Dulce (Sweet River), one of Guatemala’s principal tourist attractions, has witnessed the development of a transcendental conflict over land. Conflicts have arisen in the region where basic survival needs of entire communities cross paths with environmentally protected areas and business. On March 15th, a violent incursion by combined police-military forces ended with the tragic extrajudicial execution of local peasant leader Mario Caal Bolom.

From Mimundo.org

The imposing Rio Dulce (Sweet River), a spectacular body of water which connects Lake Izabal with the Caribbean port city of Livingston, measures approximately 35 kilometers (or 22 miles) in length. Such trajectory is without a doubt one of Guatemala’s principal tourist attractions. Nevertheless, this same area has witnessed during the past month the development of a transcendental conflict which, appropriately analyzed, reveals the somber truth beneath current Guatemalan internal affairs.

The imposing Rio Dulce (Sweet River), a spectacular body of water which connects Lake Izabal with the Caribbean port city of Livingston, measures approximately 35 kilometers (or 22 miles) in length. Such trajectory is without a doubt one of Guatemala’s principal tourist attractions. Nevertheless, this same area has witnessed during the past month the development of a transcendental conflict which, appropriately analyzed, reveals the somber truth beneath current Guatemalan internal affairs.

“At the bottom of this conflict we can find a number of intertwined economic interests for the use of land in the region where basic survival needs of entire communities cross paths with environmentally protected areas as well as tourist projects. Additionally, powerful interests in mining, livestock, and the agricultural development of African Palm [presumably for bio-fuels], also play important roles in the area. This is just one more of the many conflicts which have arisen in Izabal which underline the urgent need to find a solution for the agrarian land problem – one which has been a source of conflict in successive governments.” (1)

“At the bottom of this conflict we can find a number of intertwined economic interests for the use of land in the region where basic survival needs of entire communities cross paths with environmentally protected areas as well as tourist projects. Additionally, powerful interests in mining, livestock, and the agricultural development of African Palm [presumably for bio-fuels], also play important roles in the area. This is just one more of the many conflicts which have arisen in Izabal which underline the urgent need to find a solution for the agrarian land problem – one which has been a source of conflict in successive governments.” (1) On March 15th, combined police-military raids took place in communities affiliated to the local peasant organization named Encuentro Campesino (Peasant Encounter). In La Ensenada Puntarenas Hamlet, the violent incursion ended with the tragic extrajudicial execution of local peasant leader Mario Caal Bolom by the State security forces. (Photo of Mario Caal’s body as he was found: Anti-Imperialist Block). (2)

On March 15th, combined police-military raids took place in communities affiliated to the local peasant organization named Encuentro Campesino (Peasant Encounter). In La Ensenada Puntarenas Hamlet, the violent incursion ended with the tragic extrajudicial execution of local peasant leader Mario Caal Bolom by the State security forces. (Photo of Mario Caal’s body as he was found: Anti-Imperialist Block). (2)

“Although the media and official State vision have personified and focused the conflict in Izabal around the figure of Ramiro Choc and his supposedly criminal activities, it is necessary to take a close look at the structural factors of the conflict: First, the unequal distribution of land and wealth, both at national and local levels. One can only expect serious conflicts, even violent ones, in a country where 2% of the land owners posses 62.5% of the surface, while 94% of the population (including the indigenous peasants from Izabal) only have access to 18.60%.” (3)

“Although the media and official State vision have personified and focused the conflict in Izabal around the figure of Ramiro Choc and his supposedly criminal activities, it is necessary to take a close look at the structural factors of the conflict: First, the unequal distribution of land and wealth, both at national and local levels. One can only expect serious conflicts, even violent ones, in a country where 2% of the land owners posses 62.5% of the surface, while 94% of the population (including the indigenous peasants from Izabal) only have access to 18.60%.” (3)

During the wake and burial of Mario Caal Bolom, several community members of La Ensenada Puntarenas shared their experiences and views of the regional problematic as well as the violent events in their community.

During the wake and burial of Mario Caal Bolom, several community members of La Ensenada Puntarenas shared their experiences and views of the regional problematic as well as the violent events in their community.

“No, Gentlemen. We are a community with a history, with facts. We are a peasant group which did not organize itself yesterday. Hence, we deeply feel the spilling of blood of our friend and neighbor. We hope the State of Guatemala assumes its responsibility. Our brother Mario left a family; he left children behind; he left a number of responsibilities. Who will look after them now? What will his children do now? What about his wife?” (5)

“No, Gentlemen. We are a community with a history, with facts. We are a peasant group which did not organize itself yesterday. Hence, we deeply feel the spilling of blood of our friend and neighbor. We hope the State of Guatemala assumes its responsibility. Our brother Mario left a family; he left children behind; he left a number of responsibilities. Who will look after them now? What will his children do now? What about his wife?” (5)

“The Police and Army charged into our community in a violent manner directly against us. They broke into our homes, smashed windows, and mistreated our women. [The State security forces] believed [the Belgian tourists] withheld were here, but they were mistaken. We as a community specifically denied participating in their restraining. Why didn’t they enter our community peacefully to dialogue first? Even the representative from the Human Rights Ombudsman Office (PDH, in Spanish) was physically beaten. The Government of Guatemala has carried out a terrible injustice.” (6)

“The Police and Army charged into our community in a violent manner directly against us. They broke into our homes, smashed windows, and mistreated our women. [The State security forces] believed [the Belgian tourists] withheld were here, but they were mistaken. We as a community specifically denied participating in their restraining. Why didn’t they enter our community peacefully to dialogue first? Even the representative from the Human Rights Ombudsman Office (PDH, in Spanish) was physically beaten. The Government of Guatemala has carried out a terrible injustice.” (6)

Mario Caal Bolom was 29 years old and belonged to the Educational Commission of the Community Committee for Development.

Mario Caal Bolom was 29 years old and belonged to the Educational Commission of the Community Committee for Development.

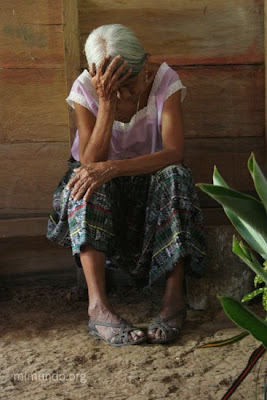

Mario Caal’s relatives, including his mother, painfully grieve as community members carry his coffin towards the cemetery.

Mario Caal’s relatives, including his mother, painfully grieve as community members carry his coffin towards the cemetery. According to eyewitnesses, the death of Mario Caal was not accidental, but in fact an “extrajudicial execution by members of the National Civil Police (PNC) who knew Mario was a community leader and because he expressed himself well in Spanish.” (It is important to note that most Maya Q’eqchi’ indigenous peoples speak a limited amount of Spanish; some none at all). Additionally, Mario served as an observer during the liberation of the 29 police officers withheld at nearby and fellow Encuentro Campesino member community Creek Maya in late February. Considering all these factors, local community members are convinced that Mario was previously pointed out by the security forces and therefore his death was by no means accidental. (7)

According to eyewitnesses, the death of Mario Caal was not accidental, but in fact an “extrajudicial execution by members of the National Civil Police (PNC) who knew Mario was a community leader and because he expressed himself well in Spanish.” (It is important to note that most Maya Q’eqchi’ indigenous peoples speak a limited amount of Spanish; some none at all). Additionally, Mario served as an observer during the liberation of the 29 police officers withheld at nearby and fellow Encuentro Campesino member community Creek Maya in late February. Considering all these factors, local community members are convinced that Mario was previously pointed out by the security forces and therefore his death was by no means accidental. (7) “Do you really think we are such idiots that we do not think things over? No Gentlemen, do not make that mistake about us. It is true, we are poor and humble. But we are not incapable. We truly hope the State has the capacity to provide meaningful information about the PNC and Army members who violently entered here in Puntarenas. Even though we see this as a difficult task as everyone is trying to wash their hands from the blame.” (9)

“Do you really think we are such idiots that we do not think things over? No Gentlemen, do not make that mistake about us. It is true, we are poor and humble. But we are not incapable. We truly hope the State has the capacity to provide meaningful information about the PNC and Army members who violently entered here in Puntarenas. Even though we see this as a difficult task as everyone is trying to wash their hands from the blame.” (9)

Meanwhile, both the Presidency and the PDH admitted that State security forces captured three peasants, including Ramiro Choc’s wife, without previous orders of arrest and eventually exchanged them for the release of the Belgian tourists. (11)

Meanwhile, both the Presidency and the PDH admitted that State security forces captured three peasants, including Ramiro Choc’s wife, without previous orders of arrest and eventually exchanged them for the release of the Belgian tourists. (11)

“The population of Puntarenas suffered a complete psychological stomping. People here now live in fear. When a coast guard boat speeds by, or community members see Police officers, they feel like running into the jungle and hide.” (13)

“The population of Puntarenas suffered a complete psychological stomping. People here now live in fear. When a coast guard boat speeds by, or community members see Police officers, they feel like running into the jungle and hide.” (13)

“Here, we are condemned. We find ourselves in an alley without exit. There are no opportunities. On the contrary, opportunities are taken away from us on a daily basis. Oppression continues everyday. In which security force are we to trust if the Police are the same ones who kill us? Only in the time of military dictatorships did things like this occur, like in 1982. Hence, it is very difficult to remember and accept… We are genuinely worried about our welfare and safety. I believe history will judge. Let justice punish. Allow the truth to condemn.” (14)

“Here, we are condemned. We find ourselves in an alley without exit. There are no opportunities. On the contrary, opportunities are taken away from us on a daily basis. Oppression continues everyday. In which security force are we to trust if the Police are the same ones who kill us? Only in the time of military dictatorships did things like this occur, like in 1982. Hence, it is very difficult to remember and accept… We are genuinely worried about our welfare and safety. I believe history will judge. Let justice punish. Allow the truth to condemn.” (14)

Versión en

español aquí.1 Reynolds, Louisa. “Izabal es nuevamente escenario de conflictividad agraria”. Inforpress Centroamericana, No. 1742. 29/02/2008.

2 Perdomo, Edwin. “Izabal: Controversia por campesino muerto durante la incursión de la fuerza pública”. Prensa Libre, Guatemala, March 17, 2008. http://www.prensalibre.com/pl/2008/marzo/17/226849.html

3 Cabanas, Andrés. http://www.albedrio.org/htm/articulos/acabanas-079.htm

4 Interview with the Auxiliary Mayor of La Ensenada Puntarenas; March 18, 2008.

5 Interview with first resident of La Ensenada Puntarenas who prefers to remain anonymous; March 18, 2008.

6 Ibid.

7 Interview with second resident of La Ensenada Puntarenas who prefers to remain anonymous; March 18, 2008.

8 Interview with third resident of La Ensenada Puntarenas who prefers to remain anonymous; March 18, 2008.

9 Ibid.

10 “No hubo canje de capturados por rehenes, asegura ministro de Gobernación”. Prensa Libre, Guatemala, March 18, 2008. (http://www.prensalibre.com/pl/2008/marzo/18/227321.html).

11 “Secuestradores canjean a turistas por campesinos”. elPeriodico, Guatemala. March 16, 2008. (http://www.elperiodico.com.gt/es/20080316/pais/50586/).

12 Perdomo. Op. Cit.

13 Interview with fourth resident of La Ensenada Puntarenas who prefers to remain anonymous; March 18, 2008.

14 Ibid.

15 Interview with member of Guatemalan human rights organization who prefers to remain anonymous; March 20, 2008.